This article is part of blog post series, Policy Actions for Racial Equity (PARE), which explores the many ways housing policies contribute and have contributed to racial disparities in our country.

Mitakuyapi, (my relatives) when I was asked to write this blog about the historical policy effects on my Native people I was immediately excited and thought to myself “simple, piece of cake.” But as I began to put this blog together it became far from simple. I started examining the timeline that the federal government had for Indian and Alaska Native Housing history and the policy development that has shaped the Native American Housing “situation” of today.

On our reservations we experience lack of housing stock, poorly constructed houses due to nonexistent building codes and enforcement of said codes, and health disparities such as increased occurrence of upper & lower respiratory illnesses in our communities. These health and safety factors are often exacerbated by overcrowding. For a short time in my life, I lived with 13 people in a 3 bed, 1 bath house in one of the worst housing clusters in the nation on the Pine Ridge reservation. I have wonderful memories of that time, but when I focus on the sanitary aspects of that situation, it creates worry in me, knowing that the life expectancy for males on the reservation that I come from is 47. This is not fiction but a stark reality for us. Eleven men that I grew up around have made their journey to the other side this year.

Much of this situation is the direct consequence of the many land and housing policies passed over the history of the United States to isolate and subjugate Native people. In this vein, I attempt to provide a brief overview of key policies ranging from 1823-1924 for you here (subsequent policies will be covered in a future blog). If you would like to dive more deeply into this, please see the resources that we have curated and included in our Native Homeownership Curriculum.

Indian Removal Act And Marshall Trilogy Supreme Court Legal Cases Decided

The first major step to relocate American Indians came when Congress passed, and President Andrew Jackson signed, the Indian Removal Act of May 28, 1830. This was followed by the Marshall Trilogy, a series of Supreme Court cases that became the foundation for key elements of federal Indian law policy, including the trust relationship. In the case of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), where the Cherokee Nation was trying to stop the removal of the Nation from Georgia, the Court held that Indians were not foreign nations, but “domestic dependent nations” – small nations that have accepted the protection of a larger nation, yet still retain their sovereignty. It referred to a “guardian/ward relationship” meaning we were viewed like children and the decision in this case would set precedent for future legalities.

Fort Laramie Treaties 1851, 1868 And The Fallout

In the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S agreed to recognize tribal authority and give aid to the Indians in return for the guaranteed safe passage of migrants. The treaty outlined the rights and responsibilities of both the American Indians and the United States. Unfortunately adhering to this treaty was complex and created a lot of chaos. This caused the US to approach the Tribes in 1868 to sign the second Fort Laramie Treaty, which clearly guarantees the sovereignty of the Great Sioux Nation and ownership of our sacred Black Hills, as well as land and hunting rights in the neighboring states. The new deal also promised that the Powder River country would be closed to all whites, with legal control over this land. Once gold was discovered in the Black Hills, however, the military was brought in to gain control of the area in violation of the treaty. This conflict led to the Battle of Little Bighorn, and following that defeat the Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act of 1876, which required the Sioux to cede the Black Hills or starve under siege. After a year of holding out, we ceded the land to the government, though we have never ceased the fight to return the Black Hills.

The policies and other treaties that ensued were nothing more than giant real estate transactions where we would cede land claims to a territory in exchange for a smaller piece of said territory that was already in our possession. The United States government began coming to us with these “new deals,” starting with the 1851 Treaty of Ft Laramie. This was the beginning of the “reservation system.” The purpose of the reservation system was, for the most part, to remove land from the Indians, force assimilation to European ways, and to separate the Indians from European settlers.

Forced Assimilation — Indian Boarding Schools And The Dawes Act

The Dawes/Allotment act of 1887 was designed for Native assimilation and to break up our tribal structure, though it ended up as another scheme for our land. The Dawes/Allotment Act, in exchange for citizenship, took our land, fractionated the land into individual plots allotting to the male head of household 160 acres and, what was left over was deemed “surplus” and open to purchase for white homesteaders. The reservation system was nearly destroyed and from the beginning. We violently opposed this “new deal” because we understood what it meant to our way of life.

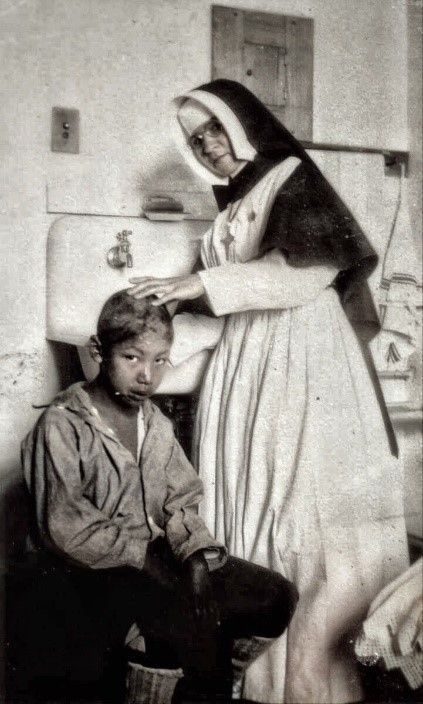

With our land rights revoked, the next step in the assimilation mission was to end tribal affiliation, mostly by targeting our youth. Between 1889 and 1960, there were 357 Indian boarding schools operating in 30 states. By 1926, approximately 83 percent of Indian school-aged children were attending boarding schools throughout the United States. General Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, stated: “The only good Indian is a dead one.”

The often traumatic and long-lasting effects the Indian boarding school experience has had on survivors and their descendants resonate in Native communities to this day. In November 2019, I helped facilitate a Historical Trauma training in Sisseton, South Dakota, which the Tribal Housing Authority had put on for their employees after a housing maintenance worker had committed suicide while on the job. The public was also invited to attend. During the session, the question was posed to me “There are members in our community that are asking, this is a mental health issue, so why is the Tribal Housing Authority putting this training on?” my response was…

“You ask any Tribal police officer on any reservation in America about the different calls that he or she responds to in our communities and the response will be mainly domestic violence issues including spouse, rape, incest, amongst others. We didn’t have these types of abuses in our communities before the boarding schools but now after a few generations of our relatives attending those schools the abuses they experienced run rampant on our reservations, so I commend the housing authority for thinking outside the box and addressing the root of those issues.”

We encourage all who believe in creating a just society to read, discuss, and share the PARE blog series as we learn and act to address the impacts of housing policies on racial equity in America. We also invite you to join us in this conversation, by suggesting additional topics and sharing resources for how we can advocate for greater racial equity. If you’d like to offer feedback on our body of work, please reach out to the Public Policy team. You can also check out our blog and subscribe to our daily and bi-weekly policy newsletters for more information on Enterprise’s federal, state, and local policy advocacy and racial equity work.