This article is part of our blog post series, Policy Actions for Racial Equity (PARE), which explores the many ways housing policies contribute and have contributed to racial disparities in our country.

As our colleague Rachel Bogardus Drew acknowledges in A Very Brief History of Housing Policy and Racial Discrimination, pre-20th century land and housing policies are the root of many of the existing racial disparities in housing that exist in present day.

The legacy of racism that began when European colonizers claimed lands through the persecution, murder and enslaving of its indigenous inhabitants and was furthered by the kidnapping and enslavement of people from the continent of Africa and their descendants, did not end with the Civil War. Instead, it has been scaffolded by a number of policies put in place post Reconstruction and continues to create substantial challenges to Black communities in rural America in the present day. In this blog, we attempt to connect the dots from slavery to Jim Crow, to voter disenfranchisement and the reasons present-day persistent poverty counties and areas of deep disadvantage in rural America overlap so heavily with communities of color.

This historical overview is brief out of necessity and does not address every practice that federal, state and local governments actively or passively used to disadvantage or discriminate against Black people in rural areas, but what they do make plain is that we cannot fully understand the inequities facing our communities of color today without at least acknowledging the history that got us here. This analysis focuses particularly on the history of the Mississippi Delta.

What is Rural America?

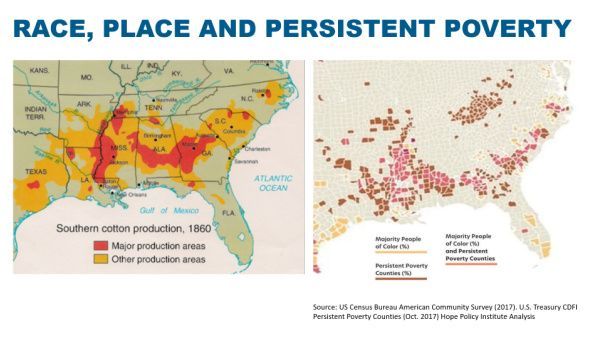

“Rural” has many different definitions and Rural America varies widely by economic base and geography. Rural can be broadly defined as non-metropolitan or non-urban and is often thought of as largely white. Data shows that many of the country’s pockets of persistent poverty are both rural and, in the rural south, disproportionately Black. In order to understand why, we must look to our history, which lays out a clear connection from concentrations of slavery dating back to the mid-1800s and to concentrations of persistent poverty today.

Connecting the Cotton Belt and Persistent Poverty

When you compare maps of counties with persistent poverty to a historical map of the concentration of enslavement from the 1860 census, there are striking similarities. Looking at the maps, it’s almost impossible to conclude that poverty and deep disadvantage are not directly tied to race and discrimination based on race. Most rural counties where severe poverty persists are predominantly counties where people of color are the majority.

Post-slavery, the Legacy of Sharecropping and the Beginning of Jim Crow

Many legislative enactments following the Civil War, that should have provided recently enslaved African Americans in the Mississippi Delta with opportunities for the acquisition of real property, were thwarted by opponents and shattered by a president who was sympathetic to a platform of white supremacy. The broken promise of “Forty acres and a Mule” meant that without land, many rural Blacks were forced into sharecropping arrangements to make a living.

At its inception, sharecropping in the Delta held the promise of a decent standard of living and independence for formerly enslaved Blacks who owned no land or farm equipment, but in practice, white land owners exploited the system to their advantage, and sharecroppers often wound up in debt at the end of each year. While Delta planters enjoyed great prosperity, their tenants were stuck in an endless cycle of debt. As plantations consolidated and centralized, what little opportunities existed for economic mobility for Blacks in the Delta dwindled. The segregation and disenfranchisement laws known as "Jim Crow" affected almost every aspect of daily life, mandating “separate but equal” segregation of schools, and other public goods like parks and libraries.

The Great Migration

Lack of economic opportunity compounded by the threat of racial violence loomed over the South and spurred many to move north seeking jobs in the industrial sector. Migration was also spurred on by the lack of educational opportunities in the Delta. Between 1910 and 1970, approximately 6 million Blacks went North, leaving sharecropping behind. By the end of World War II, much of cotton farming had been mechanized, and sharecroppers were thrown off the land.

With African Americans leaving in large numbers and the price of cotton falling, Mississippi planters and white businessmen worried about their economic stability. “Citizens Councils” were formed to further ensure that Blacks would be blocked from economic success. Mississippi was among the last Southern states to integrate the schools and allow Blacks to vote and even then, systematic disenfranchisement through gerrymandering and voting restrictions designed to suppress the vote, remain in place to this day. The use of local property taxes as the main source of public education funding also systematically maintains racial inequity and compounds a long history of separate and unequal education that includes the founding of land-grant universities.

It is also important to note that African-American, Native American, and Hispanic American farmers were systematically denied the loan, grant, land use, and technical supports that the agency provided to white farmers for decades (e.g. USDA settlements and claims processes).

The Consequences of These Policies and Actions Are Clear Today

Since the 1960s, when poverty rates were first officially recorded, the incidence of non-metro (rural) poverty has been consistently higher relative to metro (urban) poverty. Today the Mississippi Delta region has some of the highest concentrations of child poverty in the country. We must acknowledge the history of a place and of a community and the role our government played in creating the seemingly insurmountable challenges facing BIPOC communities in areas of persistent poverty.

In 2018, all the extreme poverty counties were in rural America. According to USDA’s Economic Research Service and evidenced by the maps above, these counties are not evenly distributed, but rather are geographically concentrated and disproportionately located in regions with above-average populations of racial minorities, including the Mississippi Delta. Adequate housing at affordable prices is lacking in many parts of our nation. In rural America, it's both prices and the terrible condition of existing homes and lack of adequate infrastructure, including Broadband, that present problems. The rural poor are more easily ignored, and that is compounded for rural communities of color that have been systematically disenfranchised. Historically, rural communities of color that struggle with poverty receive less help and recognition, and as a result, many in rural areas suffer silently and alone.

As Amanda Gorman said in her poem "The Hill We Climb," “And the norms and notions of what 'just' is isn’t always justice.” We cannot continue working with the confines of what “just is,” and expect things to change.

Authors Tony Pipa and Natalie Geismar state in the recently published Reimaging rural policy: Organizing federal assistance to maximize rural prosperity, “As rural communities adapt to 21st-century shifts in the national and global economy, demographics, and climate, the fallout from COVID-19 and the attention to racial injustice adds new urgency to their situation. In a nation where long-term poverty and economic distress concentrate disproportionately among people of color in rural areas, it is impossible to disentangle rural development from efforts to promote economic and racial justice. It is time to consider geographic equity as a key element of a long-term equity agenda.”

We must actively target investment in designated areas of need, and we must continue to work and support those who are actively trying address the inequities of fair, decent, affordable and healthy housing in areas of persistent poverty among people of color. There are many groups in the Delta focused on doing this work and Enterprise is excited to be partnering with them as we work collectively to dismantle the enduring legacy of systemic racism in housing – in policy, practice and investment.