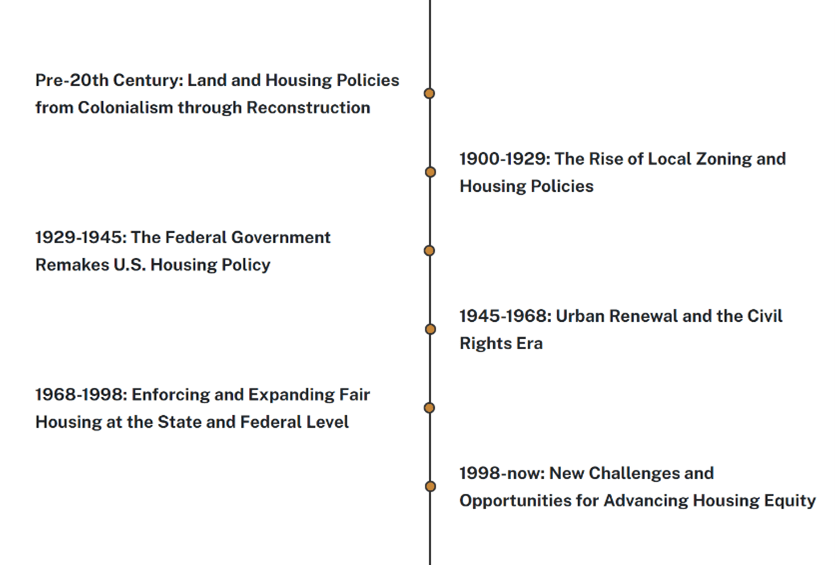

As part of our recognition of Fair Housing Month, Enterprise released a new tool, A History of Housing Policy Through a Racial Equity Lens, which provides a timeline of policy events that shaped housing outcomes for Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC) communities – from the first colonial settlements through present day. We sat down with Enterprise Senior Research Director Rachel Bogardus Drew, who developed the timeline, to learn more about how this project came into fruition and the insights she gained through the process.

When you understand how much policies of the past worked intentionally and persistently to segregate by race and ethnicity, you realize that we have to be just as intentional and persistent going forward – to not only end bad policies, but also undo the harm they caused over decades.

Rachel Drew

How did you take on this project to analyze such a robust list of housing policies over decades?

This project actually started with a blog post I wrote in December 2020, A Very Brief History of Housing Policy and Racial Discrimination, the second in our blog series, Policy Actions for Racial Equity (PARE). At a time when the country was grappling with police violence and the disparate impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on communities of color, I felt that we needed to have more conversations about the very central role that housing policy has long played in shaping disparate racial outcomes.

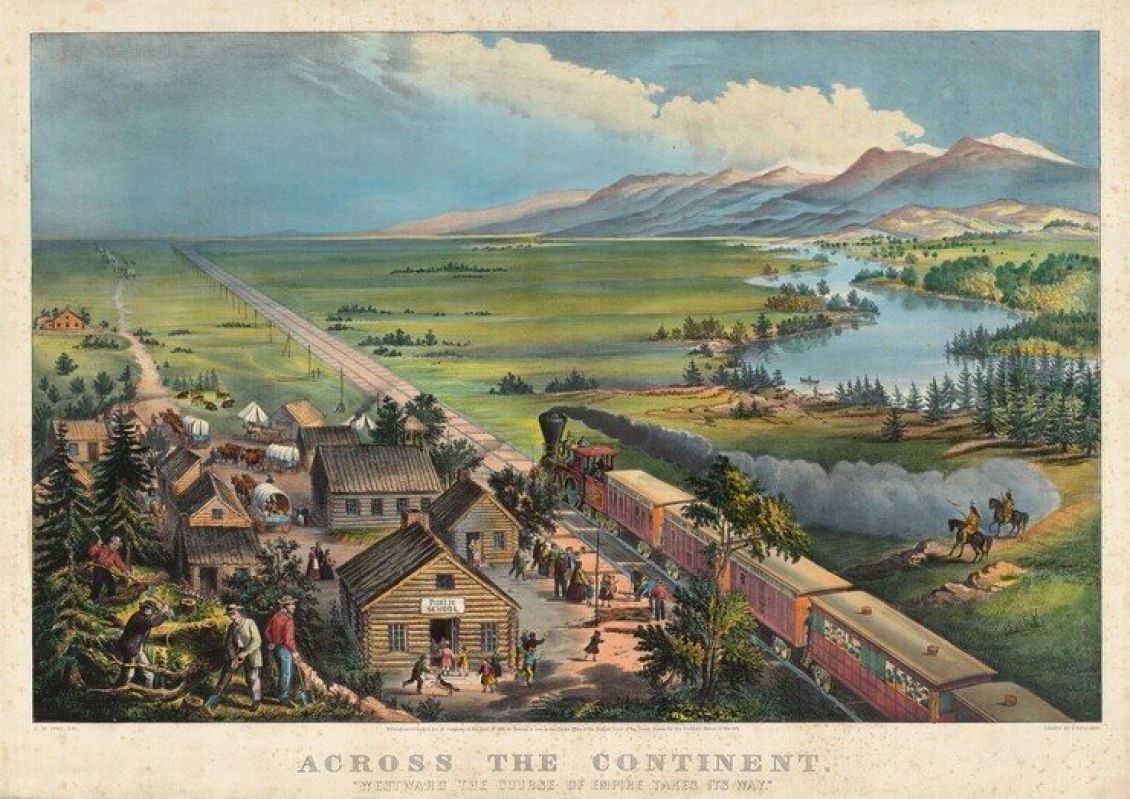

As I dug into it, I realized these policies and practices around segregating access to housing and property ownership extended much further back than commonly known, all the way to the earliest colonial era. It’s clear from the timeline that this has been a recurring, intentional theme built upon over centuries. Undoing the harmful effects will take equally intentional action over a long period of time.

Could you talk a little bit more about how housing policy relates to racial equity?

The goal of housing and land use policy is to determine where people can exist in geographic space, how groups of people can move through that space, and what activities can or cannot happen in certain spaces.

We know for example, that you don't want to put a hazardous waste plant right in the middle of a residential neighborhood, and you don't want to have highways going straight through the center of small towns. Unfortunately, we know of many instances where this has happened.

When decisions about the use of and access to housing and land becomes intertwined with decisions about where groups of people based on their race and ethnicity are and are not allowed to exist, that’s when you really start to cut off opportunity.

As a policy researcher intimately familiar with this work, what surprised you while developing the timeline?

One surprising finding was that not all historical housing policies were universally negative for racial equity. There were some early attempts, though limited, to protect the rights and access of BIPOC groups, like the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to designate land west of the Appalachians as under Native control. Ostensibly, the colonial-era policy meant to prevent white European settlers from infringing further on that territory and protect Native tribes and Native people.

That didn’t work out in practice, and the policies were later rescinded by the new United States government. Over the years, many other well-intentioned policies were likewise developed but weren’t well enforced, and they became missed opportunities that could have been built upon in more positive ways had different decisions been made at pivotal moments. Seeing these alternate possibilities in history where more equitable outcomes could have emerged was striking.

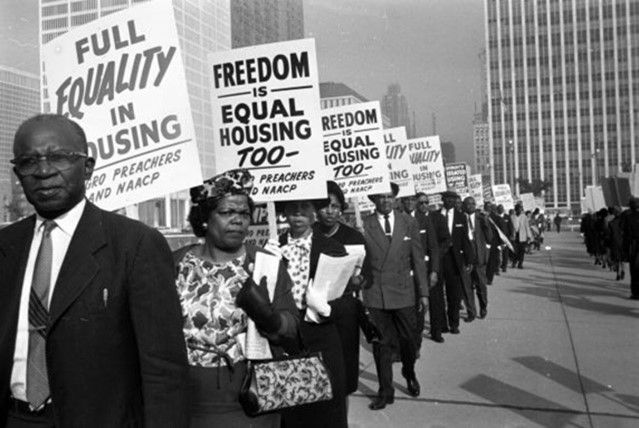

As you go forward in history, you see more and more positive attempts like the Fair Housing Act of 1968. While, at the time, it wasn’t implemented to be as effective as it could have been, from the Civil Rights era on, we finally start to see a recognition that having access to housing and land needs to be more equitable and does need to provide for BIPOC communities specifically.

It’s helpful to see the timeline note whether policies helped or hindered racial equity, or if it was a mix of both. Which policies were some of the biggest movers for good?

Some policies that stand out to me were in the years following the 1968 Fair Housing Act: the amendments to the act in 1988 and the Community Reinvestment Act in the 70s, which were in response to criticism that the Fair Housing Act was not being effectively enforced. We see examples of negative policies building on negative policies in the past, so I’m encouraged by this example of positive policies building on top of these early steps.

I’m also very interested in what’s happening on the state and local level around zoning recently. In 2018, Minneapolis was the first major U.S. jurisdiction to ban single-family only zoning, and today there are more conversations around making it easier to provide diverse housing options in communities that have traditionally tried to remain solely single family and exclusionary.

I found the era describing the rise of local zoning laws really interesting because, you’re right, it is bubbling up a lot today, and it was eye opening to see the origins of policies like single-family zoning.

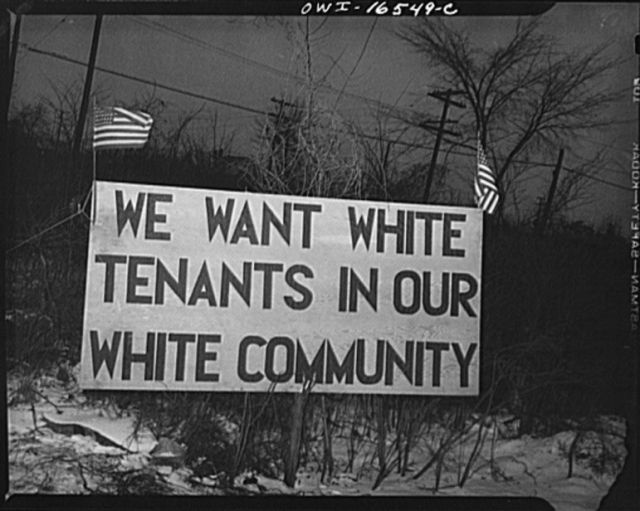

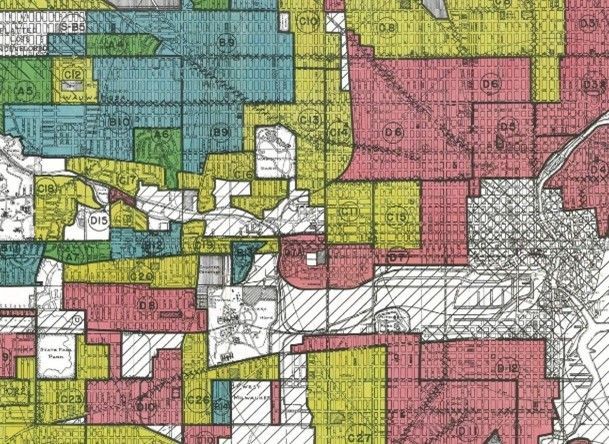

The first municipal zoning codes were pretty explicitly designed to segregate – to say, we want this type of housing in this part of town where only white households can live, and we want different housing in other less desirable parts of town because that’s where we want BIPOC groups to live.

The first single-family zoning law in St. Louis, Missouri didn’t mention race, but it drew boundaries to align with the existing and expected settlement patterns of white and Black residents. White neighborhoods were zoned for single-family homes to preserve property values and prevent Black residents from moving into the neighborhood. Some existing Black neighborhoods were classified as industrial, permitting factories and other hazardous facilities to be built there.

When you understand how much policies of the past worked intentionally and persistently to segregate by race and ethnicity, you realize that we have to be just as intentional and persistent going forward – to not only end bad policies, but also undo the harm they caused over decades.

As you noted, there are more boosts to racial equity as we move forward in history, but the timeline also makes it clear that progress is not always linear. How can we be sure the policies we advocate for today are the right ones?

You can’t move forward in the right direction if you don’t know where you’ve come from. Understanding what we as a nation and society have done in the past and the impact that has had, I hope, makes clear the importance of centering racial equity in any conversation that relates to housing and centering housing in any conversation that seeks to address racial equity. Those two things cannot be separated.

When we talk about what we want from our housing policy and outcomes going forward, we need to make sure we understand the racial equity implications to ensure they have a positive effect. And, when it comes to addressing existing racial disparities broadly – in education, health, wealth – we need to keep housing at the center of the conversation because it plays such an important role in shaping environments and access to opportunity.

Explore the History of Housing Policy through a Racial Equity Lens.