“Tell me your story.”

“Institutional responses to institutional wrong.”

“Get it together, Bowers.”

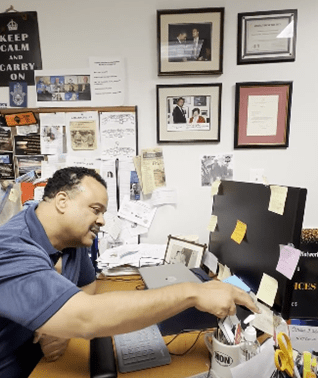

These are just a few of the quotes and “notes to self” jotted down on colored sticky notes that decorate David Bowers’ desk. Some are treasured quotes from mentors and colleagues, others come from his mother and other family members. “I may not be a sensitive guy, but I am sentimental. Each one of these quotes means something to me,” said Bowers, who is Enterprise’s vice president and market leader for the Mid-Atlantic region. “They are reminders of all the things that people have said to me, of individual stories that have mattered and still matter.”

Bowers stressed that these stories motivate him each day, even as he oversees high-impact programs and strategies ranging from the Faith-Based Development InitiativeSM to equitable transit-oriented development along Maryland’s Purple Line corridor. Referencing Enterprise’s recent milestone of creating one million homes, Bowers said, “The important numbers to look at are one million and one, because each one of these households is a story. There’s Mr. Jones and Ms. Johnson, there’s a mother, a father, a child. Each story is real – in each one of those households, people have died, and babies have been born. People have thought about how they could change the world.”

“For me, ‘tell me your story’ is one of the most powerful phrases in human language. Each of us has a story, and there’s power in each one.”

We caught up with Bowers in his office recently to learn more about his own story, the origin of FBDI, and how he weaves his background as an ordained minister into his work to create affordable homes and access to opportunity.

How did you end up working at the intersection of affordable housing, racial equity, and community development? What do you see as your core focus and purpose?

At a young age, I had a sense that I was called to ministry, but it wasn’t a call to pastoring. I knew that my work trying to make life better for people would extend beyond the walls of a church into the public service sphere. I went through college, went through seminary, got ordained as a minister, worked at a church for 14 years while I was in school, and then part-time.

But all my day jobs have been in government and community development. Capitol Hill, the Treasury Department’s CDFI Fund, the AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust, and then Enterprise. I call this work non-proselytizing ministry.

My core purpose is to help provide housing or access to opportunities for people. Two former bosses of mine each called me when this job opening came up 20 years ago. They both said, hey, there's a job at a place called Enterprise, it’s perfect for you. I thought – this must be a sign.

How have you been able to weave your background as an ordained minister into this work?

My non-proselytizing ministry serves to remind me that when there are people in need, who have real needs, we are called to try to help make life better for them from the platform where we sit. It’s played out in conversations I’ve had with leaders here at Enterprise, with government officials, and with developers.

First and foremost, I am grounded in the mission of how this is going to make life better for the people we are ultimately trying to serve. Is this helping people? How is this helping people? What is the service we're trying to render?

For me, that has played out in different ways internally and externally at Enterprise at times when I felt like that focus wasn't sharp enough. It's one of the reasons why I often recount the origin story of how Enterprise was founded, the encounter that Jim Rouse had with the three women at the Church of the Savior community – our founding DNA story. It really is grounded in three women who were moved by their faith and their sense of mission to serve, encountering a person who had the business acumen. Their focus was on helping people.

You’re a Washington D.C. native. How would you describe the housing affordability situation here? What’s unique to the D.C. area?

Housing affordability in the Mid-Atlantic region – D.C., Maryland, and Virginia – is challenging, and it's varied. D.C. and some of its’ close-in suburbs are some of the highest cost real estate markets in the country. One of the challenges stems from the dynamics between D.C. and Baltimore as anchor cities in our market. While they're only 40 miles apart, there are some big differences: Baltimore's got a big vacant and abandoned housing issue that D.C. doesn't have. The D.C. region’s median income is much higher than it is for the Baltimore region. And so that plays out in different ways in terms of costs, price points, and market pressures.

In Baltimore, it’s a classic situation where industry has left over the years, we’ve seen a loss of population, and the workforce is left with fewer opportunities. We’re left with the consequences of a lot of historical racism and disinvestment in places. Redlining literally started in the city of Baltimore.

Two of the biggest challenges in our industry are small thinking and lack of honest conversation. We’re in a region where in places like the tech corridor in Virginia, the biotech corridor in Maryland, and with the federal government right here, people are making billion- and even trillion-dollar decisions each day. Meanwhile, we have folks who are asking, can I get a $25,000 grant? We need to have more honest conversations about what it takes to help people and organizations who need the help.

How does being from this area inform the work you do here?

My work here is professional but also very personal. I’m a proud local guy. I was born at Georgetown University Hospital and grew up in Northwest D.C. My work here allows me to have an impact – to make life better - in the city in which I grew up and where I’ve lived most of my life. I love to travel, I love to see the world, and always love to come back home to D.C.

On the one hand, you could drop me anywhere in the world and I want to do things to help people. And when it’s your home, you are helping people you went to school with, where you went to a party, or where you went to pick up a girlfriend. It’s places you have driven by your whole life so it’s rewarding. And it can also make it frustrating at times because I want even more and better for my community and my home.

Let’s talk about one of your biggest and most prominent initiatives: the Faith-Based Development InitiativeSM. You headed up FBDI’s creation in 2006. Where did the idea originate and how did you get it started?

The story begins with the pastor who raised me in ministry and was my mentor, Joaquin Willis. I met him when I was seven years old. When I was leaving high school and going to college, Joaquin invited me to work in the church he started. He had a vision of developing affordable housing at the church, and even though it never came to be, I began to understand at a young age, the context, and the vision for this work.

Then, my small church merged with another church – we were predominantly Black, and they were a predominantly white church. They owned several acres of land in Maryland, and they had this image on the wall of a development that was never done, and it'd been up there for decades. At the same time, as the Collective Banking Group of Prince George’s County began, Joaquin introduced me to a number of clergy who had done economic development work and were trying to build affordable housing. Some had done it; some hadn't done it. I distinctly remember hearing one of the clergy talking about all the struggles and angst and how it literally almost killed them.

When I started at Enterprise, one of my former colleagues at the time who has since retired, Deborah Stevenson, had experience working with congregations that were thinking about developing affordable housing. Deborah and I talked to Dr. Sam Marullo, who at the time was the head of the sociology department of Georgetown University. He was doing research on how much land houses of worship owned in D.C. We also spoke with Rev. Donald Isaac. He was the leader of the East of the River Clergy, Police, Community Partnership. His organization was looking into how to provide housing for D.C. residents returning from prison. We then took a trip to Enterprise’s New York office, where we talked with two former Enterprisers - Bill Frey and Kirk Goodrich. We got some lessons from them, and we came back and launched FBDI.

What have been the challenges? How about opportunities?

First, it’s the small thinking that I mentioned – some people don't get it. There are people within the faith community who think that's not what we do. There are people in the development community, finance community, and the government investment community who say that's not what they do. Also, some people don't totally grasp how much land that faith communities, houses of worship, own in this country. It’s exciting that various groups including the Turner Center at U.C. Berkeley and the Urban Institute are now analyzing how much development could be done. In the five jurisdictions in the D.C. area alone, the Urban Institute found in 2019 that when you look at land owned by houses of worship, you could potentially build 43,000 to 109,000 affordable homes.

I call it radical common sense. You have all this need for affordable housing, health care, healthy food options and affordable day care in communities across the country. In the midst of this sea of need we have mission-aligned organizations – houses of worship – that own land that could be developed into affordable housing and community facilities.

What was unique about FBDI when we started is that it was one of the first times, we'd seen a national housing organization intentionally say, we're going to engage the faith community as partners to do this work around the country. We’re seeing that progress now. It’s becoming a national movement. We're not the only ones doing FBDI. There are other national housing and regional organizations doing this type of work now.

It’s also exciting to see the national collaboration we're doing with the Church of God in Christ. COGIC is a national denomination with their own FBDI committee. We are supporting them with their vision to support 200 COGIC congregations through cohorts designed to support the development of an estimated 18,000 affordable homes and 72 community facilities across the country. That's exciting stuff.

What do you expect to see five years from now with FBDI?

My hope is that we, as an Enterprise program and as a movement, will hit a tipping point where it’s just built into the code. Anyone who is thinking about building affordable housing will automatically ask ‘what are we doing with the faith community?’

My vision is that five years from now we'll see multiple denominations and a host of states and localities that have passed laws to facilitate this, and a much larger amount of private dollars flowing to support it. I want our program to get much bigger and stronger, while at the same time nurturing a movement that is much larger than us.

On a more local level, you have been involved in work to preserve affordable housing and economic opportunity along Maryland’s Purple Line as a major rail line is built. Why is this important?

The work along the Purple Line speaks to some big, fundamental issues and priorities that can apply to other parts of the country too. It touches on housing supply, on racial equity, and economic mobility. It’s a clear example of a major multi-billion-dollar investment in transit and all the consequences of that.

We’ve seen examples in other locations where the construction of a new subway system has led to investment in housing, but also to displacement, where people – businesses and residents – were priced out over time, business owners and residents. With the Purple Line, we have the opportunity with the Purple Line Corridor Coalition to work towards a goal of no net housing loss for 17,000 low-income households. The effort also speaks to helping local small businesses stay in place, supporting local residents with workforce development and the retention of the local culture. It's so important that our work is engaging residents, government, private sector, to make sure that we don't look up and say, oh, if we had just done this right, people wouldn't have been displaced.

You’re known for giving inspirational speeches. One of your colleagues told me recently that she was inspired by something you said last year along the lines of ‘Don’t be the thermometer, be the thermostat.’ What did you mean by that?

This is a quote originally from Martin Luther King Jr. that has always registered with me – my pastor from years ago shared it with me. It’s all about the importance of setting the tone. Are we setting the temperature? I’ve found that most people are followers, and few are real leaders. Even fewer are what I would call servant leaders, who lead with integrity and a commitment to serve others. The Enterprise mission statement I first read years ago talked about helping people move up and out of poverty. That’s transformational.

And if we help people move out of poverty, that’s about being the thermostat. It’s not just finding out what the temperature is and what’s popular, it’s about actually changing the temperature.

You have quite a few sticky notes, quotes, and photos on your desk. Why so many?

I’m inspired by people every day and it’s important to remember why. It’s critical that we remember why we are doing the work we do. Some of these reminders are lighthearted - there’s one from a former colleague that says, “A messy desk is a sign of genius.”

But some are very meaningful. I have this photo of a young lady from a school in Baltimore – Deia, she was a 5th grader. We had an event and were talking about an investment in a new school in Baltimore called 21st Century School Buildings Program. Someone asked her why she was excited about going to a newly built school and she replied, “because I like light.” Her old school was dark. I like to remember this when underwriters say no, or when funders or developers say the numbers aren’t working. We need to find a way to say yes, because someone needs a home they can afford, someone needs health care, and someone needs light in their classroom.